As the C-Suite braces for a recession, economists predict how this one will be different—and what it means for your office, your culture and your people.

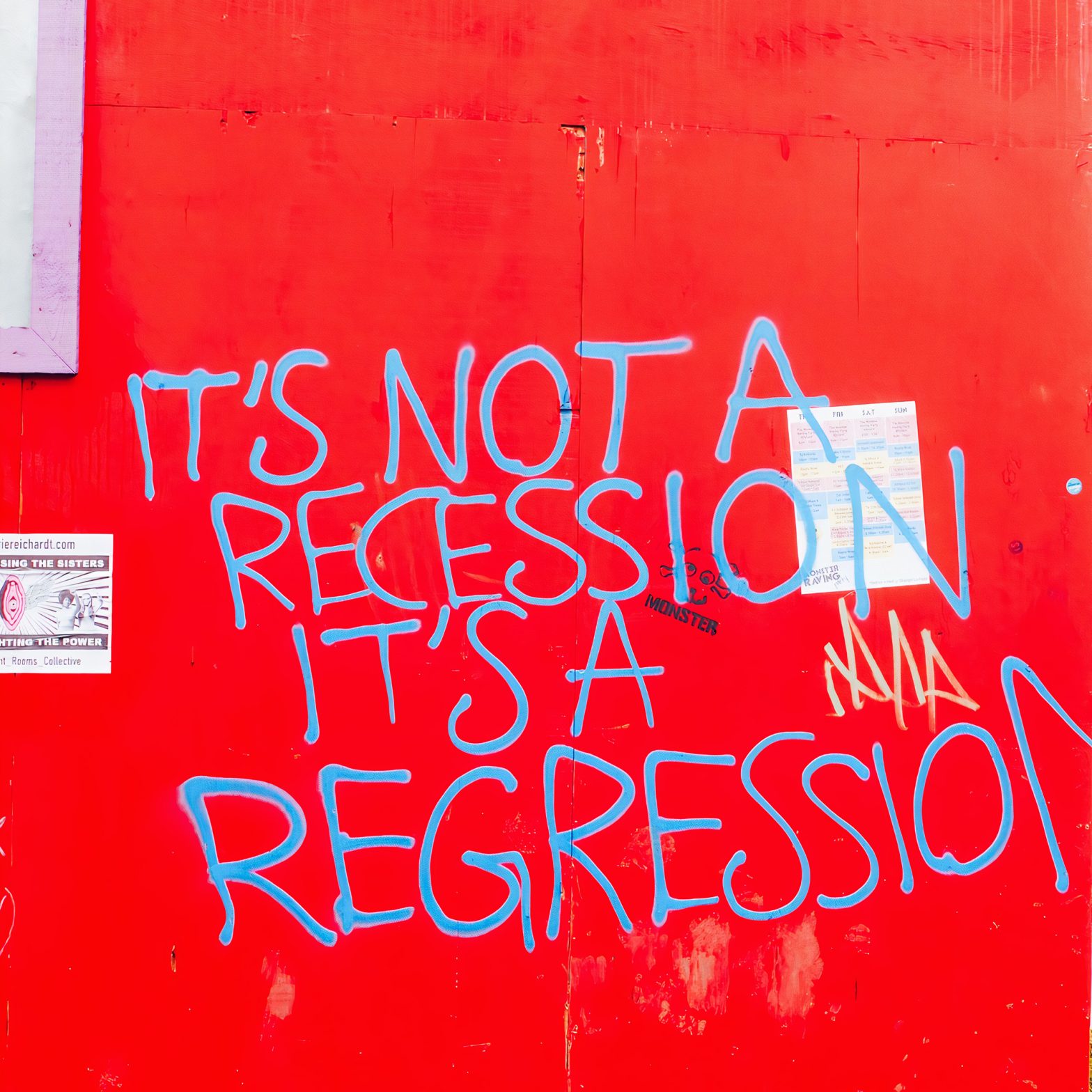

There’s been plenty of hand wringing about a potential recession, not to mention confusion about whether the economy has indeed been in a decline.

But if the economy does take a turn for the worse, the office won’t likely go anywhere. Economists say a recession would likely be short-lived and modest.

“It’s going to be different than past recessions,” says Jessica Morin, head of office research for CBRE Group, a real estate and investment firm. That’s because the economy is playing out differently than in years past: real GDP declined during the first half of this year—a sign of recession—yet we’re not seeing job losses and rising unemployment—another sign of recession.

That’s led to plenty of confusion about what exactly is going on in the economy.

Inflation and supply chain problems

The economy is certainly weird. Inflation is still raging, dropping to 8.5% in July, after hitting a 40-year high of 9.1% in June. Central banks have vowed to bring it down, but it is not easy for central banks to calibrate interest rates in a way that gently brings down inflation, writes CBRE’s global chief economist Richard Barkham in a recent report on inflation. Central banks could tighten monetary policy too much, triggering a deeper downturn.

Supply chain problems also remain. Initially caused by the pandemic, the supply chain has had continued hiccups from sudden COVID lockdowns in China and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which caused destabilization and oil, gas, agriculture, metals prices to go sky high. The cost of building services such as facilities management, engineering and maintenance has risen dramatically since the beginning of 2021, according to CBRE.

Yet at the same time….solid financials and jobs

Yet at the same time, the economy is creating an extraordinary number of jobs. July added a half a million jobs and unemployment fell to 3.5%.

Local and state governments are in good financial shape due to the American Rescue Plan Act, which put money into the coffers of state governments. “The only blemish is the federal government’s balance sheet,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics

Americans are also in better financial shape than in years past. They have low household debt, an excess of savings and while stock prices declined, their home values are up. “People are far wealthier than they were last year, and even three to five years ago,” Zandi says.

Businesses are chugging along as well. Corporate debt is low, profit margins are wide, and businesses, flush with capital, are aggressively investing. CEOs are seeing rising demand for their products, according to a survey of 1,000 public and private corporations in the Conference Board, a business and research group. Half of them expect to expand their workforces over the next 12 months and 73% couldn’t hire enough people.

Nonetheless, CEO confidence deteriorated in the third quarter with 81% of the CEOs preparing for recession over the next 12-18 months, according to the Conference Board.

Moody’s Zandi expects either job growth to slow sharply, GDP to regain its footing or some combination of both. “Boomy employment gains and falling GDP are incongruous and will not last long in tandem,” he says.

If the U.S. suffers a recession, there would be widespread layoffs by definition. But the most likely outlook is we don’t, he says, because employers will be reluctant to layoff workers given the perennial labor shortages exacerbated by retiring Baby Boomers and less immigration.

Demand for better offices

When it comes to office space, it’s clear that recessions always impact real estate markets, typically softening occupier demand and releasing excess space onto the market, increasing vacancy and lowering rents.

Morin at CBRE expects companies to look at how they can better utilize unused office space and cut costs, but she doesn’t expect the return to the office to go away.

In fact, a recession might drive more activity inside the office.

“We’re seeing a flight to quality, as companies want spaces that will attract employees into the office,” says Morin. CBRE analyzed 2700 lease transactions in the 12 largest office markets between 2019 and the first half of 2022 and found that top tier rents actually increased and landlords offered fewer concessions to tenants compared to last year. Even if there’s an economic downturn, Morin does not expect that trend to change. “It’s still about having an attractive, efficient workplace and also a healthy workplace,” she says.

Shifting balance of power

A recession could flip the balance of power to employers, after months of appealing to employee desire for recognition, flexibility and fairness amid the Great Resignation. Already leaders are starting to move away from remote work. Apple told workers this month that they must come to the office at least three days a week starting in September. Studies show one to two days in the office is the most beneficial work arrangement, yet some are starting to demand more than that.

A number of companies, including Ford, Walmart, Hootsuite, Microsoft, and iRobot, have made layoffs. The number of searches for “mass layoffs” has also increased by 1,000% since last year, according to research by software firm Conductor.

The 2022 State of Workplace Empathy Study found that many executives are eager to return to in-person work, with 19% preferring an all in-person workforce model and only 4% preferring a fully remote model. Employees, meanwhile, want to ensure work-life balance and flexibility.

“Employees are saying that all of the sudden, it’s as if some kind of switch has been flipped,” says Gena Cox, an organizational psychologist and author of the book, Leading Inclusion: Drive Change Employees Can See and Feel. “It’s going to have a chilling effect because people need a paycheck.”

The trend also follows a backlash among employees over remote monitoring software used by a growing number of companies to keep tabs on out-of-sight workers. More employers are using such software to monitor workers, recording them and ranking them.

“There is still a lack of trust of remote workers despite study after study that shows productivity gains from remote work,” says Dan Schawbel, managing partner of Workplace Intelligence, and author of Back to Human: How Great Leaders Create Connection in the Age of Isolation.

No jobs to cut

If the economy does move into recession, low- and middle-income households will be hit harder and there will be millions of job losses. Yet economists don’t expect widespread layoffs. Population growth across the country has ceased, and there have been fewer young people to fill jobs vacated by retiring Babyboomers.

Employers will likely rid empty job postings before they start laying off employees. And after months of trying to find and keep workers, they may be less inclined to cut jobs.

In preparation of a downturn, some technology companies announced hiring freezes and layoffs, and have already paused some planned office expansion and build-outs of their office spaces in such markets as New York City and Washington DC. But aside from those companies, Morin of CBRE expects tenants will continue to lease office space. And in particular, that demand will be high for high quality and flexible office space—which lets organizations expand and contract based on whatever the economy might be doing at the time.

Yet, if the last two years have taught leaders, anything can change in an instant. In 2020, we fell into a recession that was deep, but it was the shortest on record at just two months. The next year, everything flipped: real GDP grew at the fastest pace for any year since 1984.

“There used to be a belief that all recessions were the same,” says macro economist James Feigenbaum. That belief, he says, was wrong. “We’re kind of making things up as we go along.”