This scrappy art lab has become a powerful force in Facebook’s iconic office design. How? It makes art that reflects the internal pulse of the social media giant.

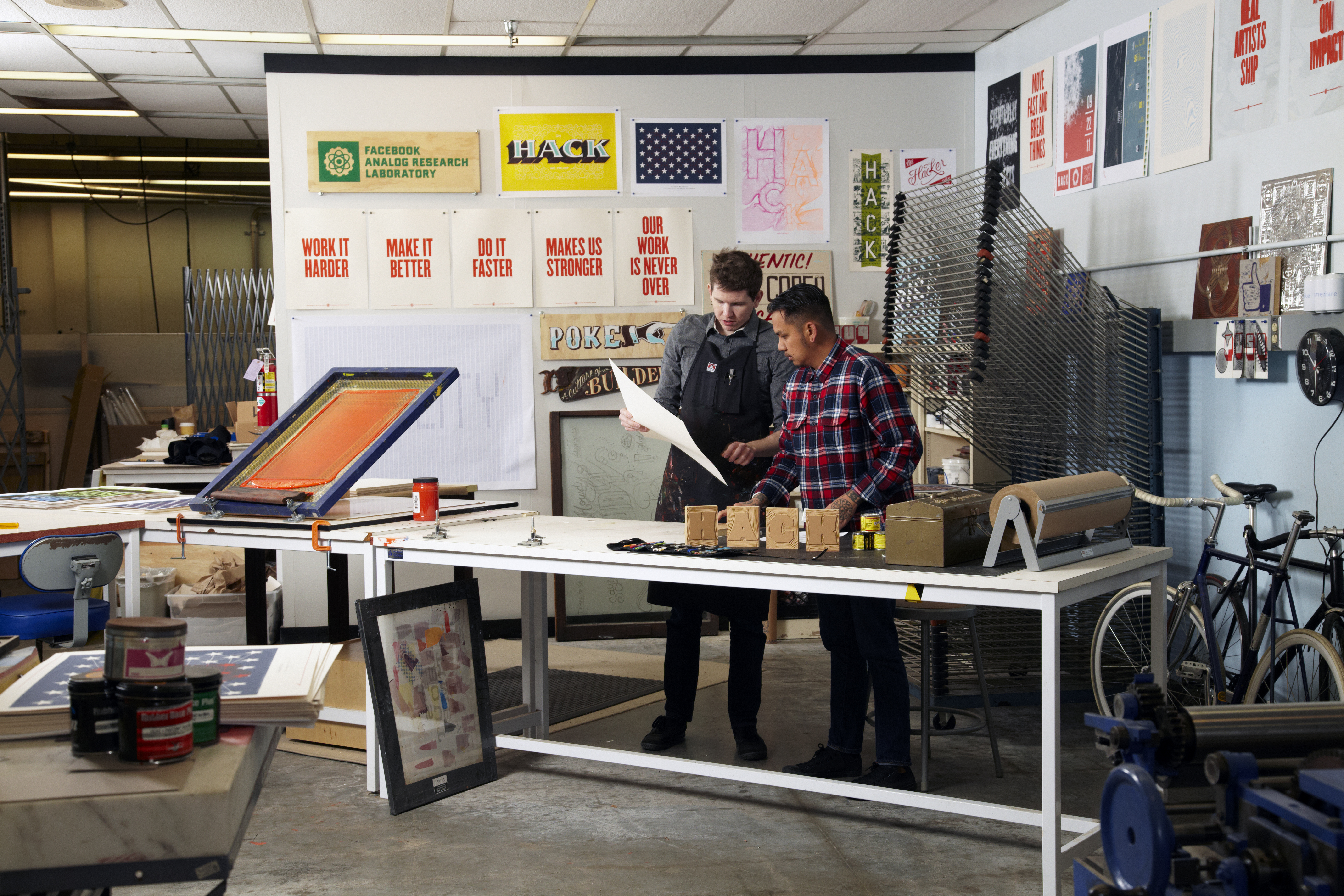

Nine years ago, two Facebook employees, Ben Barry and Everett Katigbak, set up an unusual shop inside an extra warehouse space tucked inside Facebook’s Palo Alto offices. The two marketing managers shared a passion to build a place to create hand-made art: printmaking, more traditional graphic design and illustration.

It was the exact opposite of everything else that was so digital at Facebook. It required using a different side of their brains, one that opened up different possibilities and ways of solving problems. They shared that simple desire to reconnect to making real, tangible things — things that could exist longer than much of the digital work the company was creating, which often felt as if it could vanish very quickly.

Together, the duo scavenged, built, or bought the original printmaking equipment— some with their own money and mostly in their spare time outside of work.

That early project by the two communications team managers has since blossomed into an integral operation inside the social networking giant— one that few Facebook users see, let alone know about. That operation, dubbed the Analog Lab, began producing art and posters that strengthened the internal culture at the company and, in fact, those posters now define all of Facebook’s offices around the globe.

Initially, that small art space focused on designing signage for the first incarnation of Facebook’s annual F8 developer conference. The two employees came up with the identity and overall visual language, signage, and ephemera for the event. Says Analog Lab design lead Scott Boms: “It was a very scrappy sort of endeavor originally, and about as low-tech as you can get.”

Facebook had long embraced artwork as part of its culture, going back to 2005, when it hired graffiti artist David Choe to paint murals inside the company’s Palo Alto headquarters. The executive team loved what the Analog Lab was doing so much, it allowed it to become its own department that would carry on this artistic tradition. It began producing posters that soon permeated the offices with a real sense of design— something that went beyond mere architectural style and decoration.

The Lab’s main goal has since evolved to be much bigger— to spark conversations inside the workplace.

The Analog team took ideas and exchanges that normally might reside in the digital realm and introduced them into the physically built environment that Facebook occupied— using art. Those conversations didn’t emerge from executive management’s top-down directives, but rather, they began simply with Analog employees listening to the rest of Facebook’s rank and file.

“It’s more observations across the company,” says Boms, who calls himself a workplace philosopher. “The hope is that the artwork is more empathetic, curious and diverse, and it looks at what’s happening from a critical eye. It’s the pulse of what’s going on internally.”

Boms says the posters don’t aim to dictate what employees should think. Rather, they offer a prompt for people to think about.

“We don’t want to give them the answers,” he says. “We’re observers. We’re constantly looking to see what people are grappling with and what people aren’t asking. How to navigate things.”

Sometimes, the posters interact with each other. They may wrap around a corner or invite people to cross out words and change the words. Other times, they may be stuck to the wall with flour-and-water glue. One time in particular, the message was more vague: Artists took a bucket of paint and white-washed a wall to show it was getting messy inside Facebook. Says Boms: “We needed to clean it up.”

The company’s most iconic poster, Be the Nerd, emerged following the 2016 online exchange between CEO Mark Zuckerberg and a grandmother who posted on Facebook saying she wanted her granddaughter to “date a nerd.” Zuckerberg responded: “Don’t date a nerd, be the nerd.”

“It was immediately obvious that this was a message and an idea that people would gravitate towards. It hit all the right notes of being inclusive and positive and encouraging,” says Boms.

The early sketches for that poster were very different, much more technical looking and STEM-centric. But it quickly became apparent that such an approach might feel too opaque or not as inclusive for people not directly involved in engineering-focused roles, says Boms.

This led to the use of glasses, and by creating various styles and shapes of glasses—many connected to well-known figures— it let Facebook elevate the idea to be above a cliche. “It gave it a way to exist beyond a single moment,” says Boms, “and remain fresh and fun.”

The Lab’s work proved that its art had value, not only to the culture of the organization, but also as a way to differentiate Facebook’s offices from other high-tech workplaces you might visit. Facebook offices tend to use a lot of concrete walls and exposed pipes and wires to show that their work is still unfinished. The posters, too, make it uniquely Facebook, says Boms.

In fact, the support from the executive level is so strong that no new Facebook office opens without work from the Analog Lab. “It entirely changes how you feel when you walk into a Facebook space and speaks to the core values of the company,” he says.

One recent project included a laser cut mirror installation, created last year by artist Joseph Alessio. It sits inside the company’s Fremont office, and when you look at the piece, you see the word friend from one angle, and the word enemy from the other. You also see a reflection of yourself.

The Analog Lab spaces themselves, too, have shifted to serve the broader Facebook workforce. Employees today can take artist-led classes there to learn and develop new skills, and act as participants in evolving cultural conversations.

“We invite them into what we do,” says Boms. That, in turn, influences the value of the Analog Lab, he says.

Plus, it brings people together in the company who might not otherwise cross paths. And, Boms says, that’s good for culture. “It creates opportunities to cross-pollinate, share, and find unexpected connections, and there are few scenarios where these things happen otherwise.”

Through art, the Analog Lab found a way to drive those workplace conversations offline, and in the end, it created office space that was uniquely Facebook.